Humans can learn to use repeated visual environments to find important objects more efficiently. When the same arrangement of distracting items appears again and again, people become faster at locating the target—a phenomenon known as contextual facilitation. Previous research suggests that the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory, helps store these repeated visual contexts. However, it is not yet clear whether the hippocampus mainly learns direct links between a scene and the target’s location, or whether it also learns relationships among the distracting items themselves, which could help attention by suppressing irrelevant information.

To investigate this, we used brain imaging together with a visual search task that had two phases. In the first phase, repeated distractor layouts reliably predicted where the target would appear, allowing participants to learn and use these predictions. In the second phase, the same layouts were shown, but the target location was randomized, so the layouts no longer predicted the target and instead encouraged suppression of the repeated distractors. Performance in these conditions was compared with a baseline in which layouts were never repeated.

Using pattern-based analyses of brain activity, we found that the hippocampus contained information about both types of learning: learning the link between context and target location in the first phase, and learning the relationships among distractors in the second phase.

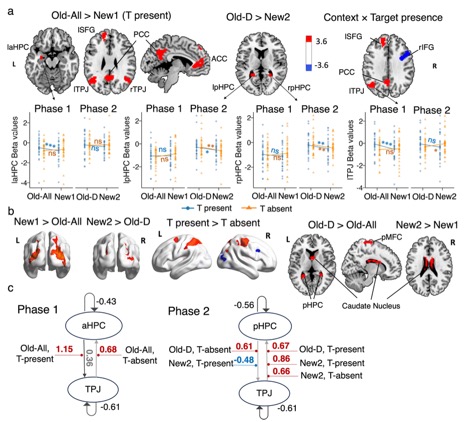

Importantly, different parts of the hippocampus were involved in these two forms of learning. Anterior and posterior hippocampal regions identified in the whole-brain univariate analyses exhibited relatively greater contributions to Phase 1 context-target and Phase 2 distractor–distractor associations, respectively.

We also found that the hippocampus interacted with the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), in different ways depending on whether the context predicted the target or not. In Phase 1, activity in the anterior hippocampal regions (aHPC) increased activity in the TPJ when the target appeared in familiar displays. This pattern suggests that learned links between the visual context and the target location helped guide attention toward the target. When the target was missing, however, the direction of influence reversed: the TPJ influenced the aHPC instead. This likely reflects the brain updating its expectations when a predicted target did not appear. No reliable effects were observed for novel displays in this phase. In Phase 2, activity in the posterior hippocampal regions (pHPC) increased activity in the TPJ, but only when the target was absent in familiar distractor displays. If the pHPC stores information about relationships among distractors, this influence may help attention by signaling that locations typically occupied by distractors can be safely ignored.

These findings indicate anatomically separable hippocampal circuits represent predictive context–target and non-predictive distractor–distractor relations, with their attentional effects gated by the TPJ.

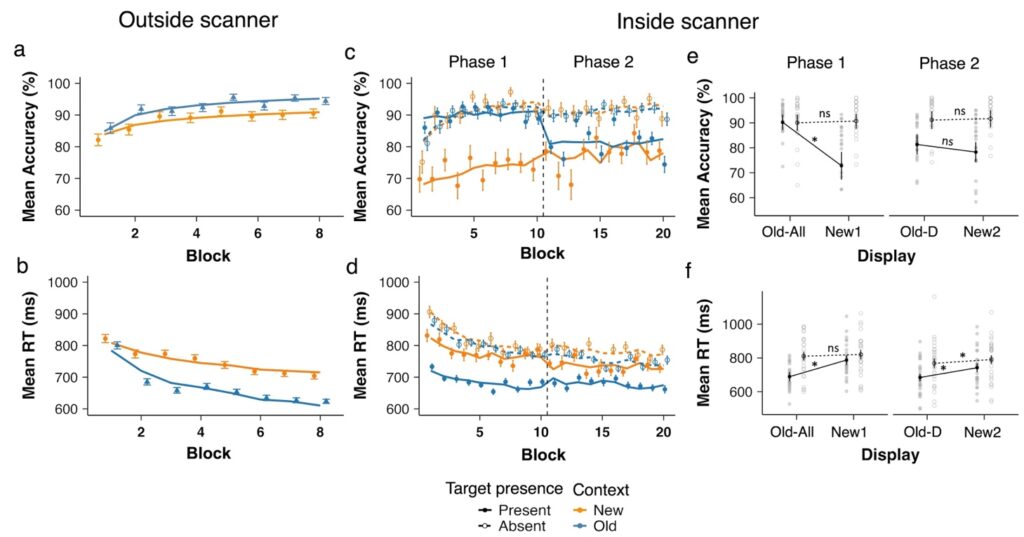

Figure 1. Behavioral results from the training session (outside the scanner) and the test session (inside the scanner). Panel (a) and (b) show mean accuracy and RTs, respectively, during the training session (1 block = 4 repetitions, 32 trials), and panels (c) and (d) depict accuracy and RTs during the test session. Data are plotted as a function of block, separately for Old and New distractor contexts and for target-present and -absent conditions during the test session. Panels (e) and (f) depict the accuracy and RT data, respectively, averaged per phase. Old contexts are labelled Old-All and the new contexts New1 in Phase 1 with fixed target locations (Block 1-10); and old contexts are labelled Old-D and new contexts New2 in Phase 2 with randomized target locations (Block 11-20). * denotes p < .01 and n.s. non-significant.

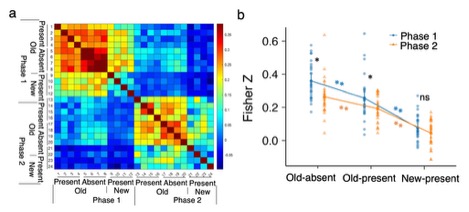

Figure 2. a Similarity matrices in the hippocampus area of correlation-based MVPA. b The mean z scores in different conditions based on the similarity matrices in a. * denotes p < .05, ** p < .01, and n.s. non-significant.

Figure 3. ROI selection and DCM. (a) Whole-brain activation maps showing significant clusters for key contrasts between experimental conditions and corresponding beta estimates comparison across experimental conditions in regions of interest: hippocampus (HPC) and temporo-parietal junction (TPJ). (b) Additional whole-brain activation maps showing significant clusters for other contrasts between experimental conditions. (c) DCM-PEB results. All connections denote a posterior probability > .95. The connectivity estimates correspond to rate constants and are expressed in units of 1/s (Hz). The grey lines with arrows depict intrinsic connections, with significant connections and corresponding parameter values shown in dark gray. The red/blue lines represent a positive/negative connection significantly modulated by the conditions. The mean modulatory parameter values are depicted in red for positive influence and in blue for negative influence. * denotes p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001, and n.s. non-significant.

This work, led by Dr. Siyi Chen, has been published in Neuroimage (2025):

Chen, S., Cheng, S., Geyer, T., Müller, H. J., & Shi, Z. (2025). Distinct hippocampus codes for contextual cueing: learning contexts and their predictive associations with targets in visual search. NeuroImage, 323(121582), 121582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2025.121582